Narrowsburg

NarrowsburgLight Rain Fog/Mist, 43°

Wind: 8.1 mph

Narrowsburg

NarrowsburgCarol Smith is the executive director of the Frederick A. Cook Society. The River Reporter asked her to write about Cook and about her work at the society for the July 2023 issue of the Upper …

Stay informed about your community and support local independent journalism.

Subscribe to The River Reporter today. click here

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Please log in to continue |

Carol Smith is the executive director of the Frederick A. Cook Society. The River Reporter asked her to write about Cook and about her work at the society for the July 2023 issue of the Upper Delaware Magazine.

Carol responded with an imagined interview conducted by her good friend, the late Tom Kane, who wrote for the River Reporter for many years.

Tom: Hi Carol, thanks for agreeing to the interview.

Carol: You’re welcome.

Tom: Can you give us a little background on Frederick Cook?

Carol: Sure. Frederick Cook was the Hortonville, NY-born explorer who went to both the North and South Poles, and circumnavigated Mount McKinley, all between 1895 and 1908. And he may have even gotten to the summit of McKinley.

He was also a gifted photographer. My relationship with him began when I started looking at his pictures.

Tom: Can you describe what you saw in Cook’s photographs that drew you in?

Carol: Well, my background is in visual art. I can’t exactly put the attraction into words, but I remember feeling like Cook experienced the world in a way that I understood—a kindred-spirit sort of thing. Allen Ruppersberg, one of my college professors, always referred to the idea of “big questions.” And there is a quote by Pema Chödrön which speaks to this sort of restlessness:

“Like all explorers, we are drawn to discover what’s out there without knowing yet, if we have the courage to face it.”

Tom: That’s a beautiful quote.

Carol: Yes. When you’re young, you kind of imagine that other people are similar to you. But at some point it becomes clear that everybody is organising their lives within different sets of values and ideas.

Cook seems to have been born with a unique view and an insatiable curiosity. There’s a great story about him as a young child living in Hortonville. He was just five years old when he wandered off to a swimming hole that he had been told not to go near, and jumped in. He taught himself to swim, but almost died in the process.

Tom: Wow—I’ve known kids who take to water easily, but the fact that he jumped—that’s quite telling!

Carol: Yes, that fearless curiosity was part of his personality.

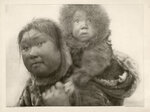

Besides being a physician and a photographer, he was also an anthropologist. He learned to speak Inuit, and lived with a number of different Indigenous tribes, from South America to Greenland. The photograph titled “Eskimo Madonna and Child” is considered one of his masterpieces.

Tom: Can you explain how you got so involved?

Carol: Well, there were a number of things that happened. The first was a letter from Julian Sancton to the Cook Society. It ended up on my desk at the Sullivan County Museum, at a time when I knew very little about Dr. Cook. Julian had just written a book about the 1897 Belgian Antarctic expedition, and he goes into great detail about Cook’s role in saving the lives of the men on that ship. I was able to help Julian get permission from the Cook Society to use some of Dr. Cook’s photos in his book. And that got me looking.

I found amazing photos in folders, many with Cook’s handwriting and signature. Also found the collection of 100-plus Alaska photos, taken around 1906, and Inuit artefacts and some amazing original documents. Like a letter from Roald Amundsen sent to Frederick Cook while he was in prison—it was stuck in a book.

Then I began to remember things I’d forgotten from my childhood. Like how I’d been mesmerised by the book “Kon Tiki,” and also Mika Waltari’s travel adventure novel, “The Egyptian.” I also remembered having had frequent dreams about shipwrecks and falling into deep crevices. And I still have a very real phobia of crossing bridges, though that probably doesn’t mean anything at all. [Smiles]

Tom: Still, it’s kind of interesting. And then what?

Carol: Well, the more I looked at the photographs, the more I got pulled in. My computer was totally filling up with Arctic and Antarctic images.

Naturally, I became curious about Dr. Cook’s life, so I started reading. The first book I read was “Return From the Pole,” Cook’s account of overwintering in an ice cave with his two Inuit companions.

Tom: Is there a way for you to articulate the connection you felt? You mentioned you have been heavily involved [with the society] now for three years… has that happened to you before? The experience of thinking you know things you’re not supposed to know?

Carol: Not really, not that often—I mean, being an artist seems to have a lot to do with intuition. And if you think about intuition—we have an agreed-upon definition, but we don’t really know what it is.

Frederick Cook was interested in things that can’t be explained, and so am I. And if you’re born that way you end up involved in activities that don’t necessarily make sense. And you can’t stop because you are trying to understand something you imagine you might find.

Tom: [Smiles] Can you give me an example?

Carol: Sure—like the North Pole. Early explorers had all kinds of wild ideas about what’s at the Pole. They speculated about everything from mythical cities and magical beings, to mountains of diamonds and gold. By the time Cook went, he knew the Pole was just shifting ice and more ice. But he went anyway, and then he became introspective about that thing which drove him to go there in the first place. And in 1913 he wrote this:

“Unless one has been to the Arctic, I suppose it is impossible to understand its fascination—a fascination which makes men risk their lives and endure inconceivable hardships for, as I view it now, no profitable personal purpose of any kind.”

Tom: That’s fascinating.

Carol: Yes, and for me, it’s pretty similar to being an artist. I mean, looking back at my career, I spent years painting and pushing myself to try and solve some mystery that I can’t explain. And I have no idea what drove me—or where those qualities came from.

Tom: So where do you go now with the Cook Society?

Carol: Well, I’m getting more familiar with Dr. Cook’s work. He wrote five books and numerous papers, and he took hundreds and hundreds of photos. But again, it’s intuitive. I feel like I have something to discover and I’m not exactly sure what it is.

Tom: And do you have plans for more exhibitions? I know you just finished redesigning the Cook Gallery at the Sullivan County Museum.

Carol: Yes, but for now I’m taking a break. There are over 60 photos currently on display, and many more that we are working to print and frame. The sled we own [pictured this page, with a photo of Cook’s tent and the Belgica], is one of the most important artefacts in polar history. It was built in Hortonville, by Cook and his brother Theodore, then taken on the Belgica expedition, where it was used by both Cook and Roald Amundsen. It’s an amazing piece of history.

Tom: Wow—that’s cool!

Any last thoughts you would like to share?

Carol: Only that Dr. Cook’s life represents some of the greatest achievements in exploration history. It feels important to tell the stories and preserve his legacy. I appreciate you taking the time to help us with our mission.

Tom: Thanks Carol; my pleasure.

For more information about the Frederick Cook Society, call the Sullivan County Museum at 845/434-8044, or visit its website at www.frederickcookpolar.org.

The museum is located at 265 Main St. in Hurleyville. The hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and Sunday from 1 p.m. to 4:30 p.m.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here